This post is an update on how our appointment went with the congenital myasthenia team at Great Ormond Street hospital. If you haven’t read the post written just before we went to this appointment it is worth popping over there and catching up before you read this one.

Sometimes in life, no matter how hard you search, you don’t always get the answer you were looking for…

By the time we were on the train home from the appointment I was exhausted. As usual we had to play guess-where-the-disabled-carriage-will-stop when we arrived on the train platform, and as usual the disabled carriage sailed straight past us and stopped at the other end of the station. It was too crowded to attempt an emergency dash to try and get to the right section of the train before the doors closed, especially pushing a wheelchair and trying to keep sight of two other short humans, so we wriggled and squeezed and pushed and apologised our way onto a busy regular carriage and spent our journey attempting to stop bags and coats walloping Dominic in the face and trying to pretend we weren’t smelling other people’s armpits.

I guess things could always be worse…

I just want to pause briefly to address the train operators in Britain- I see you are capable of telling me how many train carriages my train will have, thanks for that, it’s really helpful, and I’m sure knowing where the exact location the First Class carriage is going to be well ahead of the train arriving is useful for someone. It even scrolls along the information screen you put on the platform which is very convenient. I wonder then, why no one can tell me where the disabled carriage is going to be, no matter how far ahead of time I ask. It would be enormously helpful to not have to enter a lottery each time I pick my position on the platform, and I appreciate that you might not want to have to tap some extra digits into the information screen, but could you perhaps just put it in the same place each time, you know somewhere that makes sense, like perhaps the carriage that stops opposite the ramp? Currently travelling on the train is nerve wracking, as it seems that wherever I choose to stand, the disabled carriage ends up at the opposite end of the train. We don’t use your ramps as you have to book so far ahead and we never know when we’re coming back (length of appointments at the hospital vary so much), so I lift him on in the wheelchair. Commuters generally have little patience for small children in wheelchairs and we regularly have people stepping into the space that I’m lifting his wheelchair into so the doors close on us. The only carriage I can get the commuters to move to let us on is in the disabled carriage, but I need to know where it is going to stop on the platform. Your staff, to their credit are always embarrassed and apologetic about the situation, more so after they’ve attempted the platform dash ahead of us to try and hold the doors to the disabled carriage so we can get on, and failed to get even halfway there. It’s such a little change to make, but it would make such a huge difference to our experience. Heck, you could even develop an iPhone app and charge a (small) amount for it to cover any extra costs there might be to get the person who updates the details on the info board to add an extra line. Or perhaps you could just agree to always have a set carriage number as the disabled carriage (it would save your staff running the length of the platform with a ramp as well for the people who can book ahead). If you need anyone to help you sort this out, give me a shout. Disabled people, those with bikes and buggies would love you for it.

It was pouring with rain by the time we got off the train and any pretence of happiness dribbled down my face and off my chin along with the water. The man who decided to (almost) prevent us from getting in the lift because he couldn’t be bothered to walk up the stairs got unsympathetically pinned up against the side of the lift by my wet children who dripped mercilessly on his suit, and I do believe one of Dominic’s wheels might have been parked on one of his shoes as we all awkwardly waited the eternity it takes the station lift to travel a few foot upwards. The man very sensibly then disappeared down the stairs on the other side of the platform and we made our way down in the lift and wetly home.

The reason I let such everyday occurences bother me, when I would normally shrug them off, was because I was already miserable. Quite apart from the weather and the train journey home, I was having a teeth clenched reaction to the fact that firstly, there had been a fair amount of expectation about this hospital appointment (this is, after all my second post about it) and secondly, that expectation wasn’t met by the actual experience. It had left me annoyed with myself for failing to do something about it at the time, which in turn made me feel like I had the right to be annoyed at the rest of the world for also refusing to live up to my expectations at that precise moment in time. Thankfully (for my children) these feeling are a relatively temporary blip in the opportunistic sheen I like to polish. I generally don’t do angry, quite simply because being angry and miserable is exhausting, and I’m way too tired to be able to give any energy up needlessly, especially when it doesn’t change the situation, just makes everyone else miserable too.

A demonstration of how the angry face and pointy finger can be used to convey emotion to a small child

But for this day, at least, I was going to embrace the inner grump, but not, as you might expect because of the first appointment we had that day where the consultant didn’t even bother to turn up, but because of the one where there were four doctors in the room, all waiting for me, all smiling- a lot. We all have expectations of some sort or other when we go to see professionals about our child’s health. Most people hope that the visit will bring about a positive change, or they will gain some insight at least into what is going on. As the novelty of these visits wear off, especially if you spend lengthy amounts of time with the doctors in hospital, those expectations are adapted and managed depending on who you are seeing and what you are seeing them for.

I have written about our first appointment in a separate post, which can be found here. What came out of it, and the implications for communication between doctors and patients is interesting and important enough to not let it get lost within this post, so it got one all to itself. Do check it out when you have a minute.

The appointment that I am (finally) going to tell you about within this post is the one with the congenital myasthenia syndrome (CMS) team, and it was a meeting that, despite me having run through various scenarios in my head, turned out to be an entirely different experience than what I was expecting. At previous appointments I had been impressed by the teams efficiency and combined intellect, even if they were occasionally prone to forgetting that we were in the room which is always a little off putting. On this particular day they were no less intelligent, but rather than leaving feeling secure that my children were in good hands, I left feeling confused and wondering whether I had just witnessed an ill informed decision which didn’t just alter the direction of our journey, it made us walk smack, bang into a brick wall.

Don’t forget to clean your teeth, kids!

This was our fourth appointment with them and as far as I had been lead to believe, based on the results of various test that they had asked for, a decision was going to be made to rule out one of two diagnostic possibilities in a effort to narrow down the our search for what was causing all of Dominic’s (and a few of Elliot and Lilia’s) symptoms. It turns out that this was my expectation alone and the outcome of the appointment left me without a clear answer at all. As a result I felt rather numb for a long time after we left. It wasn’t until I was home and tiredly tackling the witching hour (my affectionate name for the dinner-bath-teeth-bed routine) that I even attempted to unravel how I felt about what I had heard in the consulting room. I knew that I had to somehow convey some sense of what I had heard to those waiting to hear what had been said, but this seemed an impossible task when I wasn’t entirely sure what had been concluded myself. If you’re planning to get dental implants to replace your missing teeth, check out Pacific Dental & Implant Solutions today.

Whilst I could safely say that I had not, in general terms, been given bad news in the appointment, I was feeling uneasy and rather disorientated which I had not been prepared for. I had mentally steeled myself for the team to tell me that either Elliot and Lilia’s muscle MRI results had showed fibres that were more suggestive of a myopathy and so the team would hand us over to someone else, or that they had not shown a myopathy that may have lead them to invite us to the congenital myasthenia camp. As it turns out, neither team wants us, so we’re just going to be sat on the bench for the season. I’m trying to not take the rejection personally. I went there expecting something to change, even if it was just a micro step forwards. I didn’t expect the doctorly equivalent of a shrug and a “I dunno” and to then have to take my piece and remove it from the game altogether .

Whilst I could safely say that I had not, in general terms, been given bad news in the appointment, I was feeling uneasy and rather disorientated which I had not been prepared for. I had mentally steeled myself for the team to tell me that either Elliot and Lilia’s muscle MRI results had showed fibres that were more suggestive of a myopathy and so the team would hand us over to someone else, or that they had not shown a myopathy that may have lead them to invite us to the congenital myasthenia camp. As it turns out, neither team wants us, so we’re just going to be sat on the bench for the season. I’m trying to not take the rejection personally. I went there expecting something to change, even if it was just a micro step forwards. I didn’t expect the doctorly equivalent of a shrug and a “I dunno” and to then have to take my piece and remove it from the game altogether .

It didn’t help that my brain had been cooked alive by the overly hot waiting room, so I was a bit gormless and glassy-eyed by the time I peeled myself off the plastic chair to go in. The five second delay between hearing the doctor expressing surprise to see all the children there and my brain registering this as not being the expected response and furrowing my eyebrows in a way that would lead her to ask what the matter was, meant that she was already onto another subject before I had a chance to process the information properly. My default assumption is that misunderstandings like this are likely to be my mistake, and so I kept quiet thinking that perhaps I hadn’t had appointments for all of them after all. It wasn’t until I was home and finally had time to think everything through that I realised that it wasn’t my mistake at all. Our last appointment had been left with their conclusion that Elliot and Lilia were far more indicative of CMS than Dominic because he was just so complex. The team had therefore decided that the testing would concentrate on them before conclusions were drawn. I also found Lilia’s appointment letter.

The team were, instead, in the middle of telling me that all of the CMS gene defaults they had tested Dominic for had come back negative, which I don’t think was much of a shock for anyone. The fact that they all sat there after telling me this with that smile on their faces, the sort of smile that people get when they are apprehensive about the way you’re going to take news that you probably don’t want to hear, made me nervous though. There seemed to be an awful lot of this smiling going on, and not much else apart from a few polite questions about how Dominic was getting on at school, by which point I was wondering if I was meant to be saying something, as this small talk in between silent smiling just seemed, well awkward.

Unfortunately my knee jerk reaction to being silently smiled at is to talk. Well talk probably implies more intelligence than what actually comes out of my mouth. What I really do in situations like this is babble. Now you may have noticed that when I write I generally adopt the approach of using a hundred words were one would do perfectly. You can imagine then what I’m like when I’m trying to fill silence, but still want to sound like I’m being vaguely relevant despite my brain having been zombified by the waiting room. It’s not pretty. There are no neat, well constructed sentences, they are basically open ended stream of consciousness garbles that normally attempt to make the person sat opposite me feel better about the situation but actually just make them think I’m on some sort of narcotics. Or insane. Or both. On this occasion, as I babbled away about how I wasn’t expecting any answers and life goes on, we’re used to not knowing, and not to worry, it occurred to me that I had been so disorientated by their surprise at seeing Elliot and Lilia at the appointment that I hadn’t even asked about their MRI results. So I stopped the incessant noise coming from my mouth and actually asked my first intelligent question of the appointment. The smiles stayed fixed, but the eyes blinked blankly back at me.

Thankfully, there was no doubt in my mind that I had got this fact right, so I quickly reminded them that they had sent Elliot and Lilia for an MRI of their muscles and we were meant to be looking at the results. One of the doctors, grasping the initiative, muttered “of course” with an admirable stab at confidence and busied herself trying to find out what the hell the results were of the tests that they had forgotten all about (but I had spent the last three months worrying about). There was more silence, as we all waited for the images to pop up on the computer. The first one looked like, well a leg of lamb if I’m honest, but apparently that is what a normal girl of 7’s thigh looks like on the inside. Elliot’s also seemed normal, I was told, with the exception of an almost undetectable lighter outer patch on his calf muscle. She didn’t think that it was significant, but thought it best to run it past someone to confirm. And then there was the silence again. A silence that I was starting to feel annoyed by now, because I didn’t understand what it meant. In my mind it couldn’t possibly mean that they thought that they had said everything that they needed to, as I still felt like they had not actually told me anything other than that a couple more genetic tests had come back clear for Dominic, and the MRIs didn’t seem indicative of a myopathy.

I started asking specific questions, but got vague answers to all of them. From what I could glean they thought that Dominic was not typical of CMS, and they had found no gene faults that they had tested for, but nothing further was offered to clarify what that meant they had concluded. So I asked how we could test to find out if it was a myopathy then, and they answered that normally a muscle biopsy is carried out. Of course Dominic has already had two muscle biopsies, neither of which showed a myopathy, which I reminded them of. They agreed. They still didn’t draw any conclusions. So I reminded them that there were plenty of patients of theirs that have undiagnosed gene faults but are still classed as CMS, which they also agreed with. So I went on to reminded them that they thought that Elliot and Lilia were more indicative of CMS than Dominic which is why they did the MRI on them in the first place, and they smiled once more and nodded as though confident that they had armed me with appropriate information and now I was merely amusing myself by asking rhetorical questions that didn’t need any further interaction from them.

I found as many ways as I could to say “and… what are you trying to tell me?”. And I’m still not entirely sure what the actual official answer is. From what I can gather, the decision has been made purely on Dominic’s results. He doesn’t present as a classic CMS child (waaaay too complex) even though the results of nerve conduction tests are indicative. The gene faults that his symptoms match most closely have been tested and are negative and so they don’t think it’s CMS (despite the fact that they readily admit that there are likely to be many more as yet undiscovered CMS gene faults and lots of CMS children are actually undiagnosed). So I asked if they thought that it was a myopathy then, to which they said that only a few myopathies affect the neuromuscular junction and they are diagnosed by a muscle biopsy. Dominic has had two muscle biopsies, both are negative. What would you guess they had concluded if that was the information you were given? I think I now have a permanent furrow where my brows joined in my confusion.

So, having gone to the appointment expecting black or white, I had instead been given a watered down shade of muddy grey. I felt, overwhelmingly, that I had come out with less information than I had gone in with though, which feels as bizarre as it sounds. The overwhelming feeling that I am left with is a feeling of doubt about the validity of what they have concluded. Having put all my children through testing, they then appear to have overlooked two thirds of their results to make a judgement using the most atypical of the evidence in front of them. It didn’t engender any trust in the conclusions they had come to, especially because I had to guess at these conclusions as they weren’t clearly communicated. One question that the doctors asked me before I left was whether or not there were any other people going to see us any time soon. I told them that I had an appointment in a year with his neuromuscular consultant. There was an embarrassed shuffling of feet while someone muttered that perhaps we should be seen by a team specialising in muscle disorders, before I repeated my good byes and left knowing that it was unlikely to happen. I do of course hope to be proven wrong.

So on paper, we are no better, and no worse off than we were. We still have no diagnosis. No clue what monsters are hiding under the bed. But I walked out feeling that we were in a worse position than before. We now didn’t even have a team who are interested in us, so it is likely to be a year or so before we even get the next review appointment with the neuromuscular team to work out what to do next. I could see the cracks, and I knew that as we walked out of that room, we would be left to fall straight into them.

If you saw the person I appeared to be as I walked into that appointment, and compared it to the person you saw thanking the doctors as I walked out, you might have noticed the difference, but struggled to pinpoint exactly what it was. I must have looked tired, certainly, but I think I walked out of there having having silently crumpled, just a little. The slump of the shoulders, the slipped smile, the tired gathering of coats and bags and good byes to the doctors, the only clue to the dawning realisation that in walking out of that room, I was leaving the remains of this little bit of hope behind.

I left with no plan, I was given no idea where to turn next, no telephone numbers of specialist nurses, no support groups, no leaflets, no information, no idea who would pick up the pieces from here. I was just left. However, I consider myself to be luckier than most of the families in my position, because I have the dubious pleasure of being a pro at this now. I’m lucky enough to have picked myself up and dusted myself off enough times to know that I can do it again. I may get more battle weary each time, but I also get more efficient at being able to shut the worry and frustration at not knowing what is wrong away and just concentrate on the life that we have at the moment. It’s a bit like having to stuff a giant, slightly deflated balloon into a small box, sometimes bits can spring out and slap you in the face when you think you’re almost there, but for the most part, if you’re determined enough, you’ll be able to shut the lid and sit on it eventually.

But this does not mean that I do not distinctly remember how I felt when we first got told that no one knew what was wrong with Dominic. He was very ill at the time, having just come out of intensive care. I have never felt so scared and so alone. The pure terror of not knowing what was doing this to my baby would give me nightmares, even when I was awake. I lived in an almost perpetual state of fear of what we would find wrong next, and whether that thing would be the one that killed him. Your imagination is always far worse than any reality could be and mine ran rampant with the grief and anxiety brought on by facing something so terrifying when I felt so helpless. I honestly don’t know how I managed to keep enough parts of myself together at that time to not to be shattered into so many pieces there would be no fixing me. I suspect the answer is simply because, like all parents, I had to.

Hindsight is a great thing, and now, when I look back and think about how fragile we were as a family, and it makes me angry, angry that there was never a thought given to what happened to us in-between hospital appointments. I was drowning in the newness of this life, a single mother and barely capable of getting out the door, let alone searching out what I was entitled to, how I could chase missing results and how I could ask for help, or even know that it was ok to admit that you needed help. I was alone, completely, utterly alone.

But the wonderful life we lead now is testament to anyone who is reading this who has just walked out of an appointment feeling like their life is in pieces. There is a way through it, and there are people who have come out the other side of it who are now kick-arse ninja versions of their former selves, even if we do still take a day off duty here and there to feel miserable every now and again.

At some point in our journey I realised that I had a choice. I could tread water, surviving, or I could do everything that I could to change things for not only my family, but also for the people just starting this journey. I can’t change the fact that their lives aren’t the ones that they dreamed of when they first found out they were expecting a baby, but I can perhaps help them to keep their head above water, and put to use some of the things my journey has taught me. We all have a choice, to use our time and energy to complain about what we don’t like about our lives, which changes nothing, or we can do our best to do something about it.

And here is how I would like to make a small change, so the families that come after me aren’t allowed to fall through the cracks and all the teams that really are trying to help start working as a unit, rather than separate parts of an inefficient system, all assuming someone else is making sure the family is ok.

Support shouldn’t start with a diagnosis

The diagnostic process can be a long and complicated journey, or it can be no more than a brief waiting period, but for all the families waiting in limbo, it is arguably one of the most difficult times in their life. The grief that parents feel when they realise that their child has a disability or a medical issue is well documented, but the effect of knowing that there is something wrong with your child but not knowing what it is or the possible long term implications is rarely addressed. We live in such a medicalised world that I understand that it can be difficult to remember that there are people who remain undiagnosed these days. It is important to remember though that if we ignore the fact that this is a reality for many families it in turn means that we are not providing support for thousands of people who are amongst the most vulnerable and isolated in our society.

What can change?

Communication is always a breaking point in the chain of care for complicated cases. For some reason, passing messages between one speciality and another can be problematic even if they are based on the same corridor in a hospital. Recognising this is key to preventing families falling through the cracks. If a team has ruled out their involvement with a patient, the care should be handed to a specific person who then facilitates the paperwork finding its way to the next step in the road. More importantly, there is someone who is a focal point for the family for questions about what happens next or what options are available. These families need somewhere to go to, even if it’s just to ask the question, what next? This support should not kick in once a diagnosis is established, but at the beginning of the journey, when they are at their most vulnerable and have the most questions. Accessing services without prior knowledge of the system is a minefield, and there are no manuals out there telling you how to do it. Add on the complication that having no diagnosis gives you with bureaucracy and it means that many families aren’t even getting the support that they are entitled to. All because they are unable to fill in a small box on a big form.

This is not a pipe dream. Other organisations already have specialist family advisors in place, funded by the NHS. Why shouldn’t families with an equal, if not perhaps greater need, be treated in the same way? Coordinating and streamlining the services for complex patients can only be beneficial to all those involved from consultants to council paper pushers, but, moreover it could be the lifebuoy that some people need to stop them going under.

How could it help?

Had any of the things been in place that I have mentioned, perhaps I would have left our appointment feeling very differently than I did. What should have happened (quite apart from the team being more prepared so I could leave feeling confident that their decision was based on all the evidence rather than a part of it), is that rather than simply smiling at me and feeling awkward that they didn’t have an answer, they should have been ready to give us information about what happens next and where I go if I have any questions or concerns after I have gone home. I should have walked out clutching a lifeline, something as simple as a leaflet telling me that there are other families out there like me at the very least.

Had any of the things been in place that I have mentioned, perhaps I would have left our appointment feeling very differently than I did. What should have happened (quite apart from the team being more prepared so I could leave feeling confident that their decision was based on all the evidence rather than a part of it), is that rather than simply smiling at me and feeling awkward that they didn’t have an answer, they should have been ready to give us information about what happens next and where I go if I have any questions or concerns after I have gone home. I should have walked out clutching a lifeline, something as simple as a leaflet telling me that there are other families out there like me at the very least.

I think that this is a reasonable minimum expectation for families who are often juggling some of the most medically complex of children. However, what has to happen first is that the medical community have to realise that families don’t go into stasis when they leave an appointment room, they go and they live their lives. And sometimes living can be utterly terrifying, and sometimes being terrified can stop you from living. The professionals involved with the diagnostic process have a responsibility beyond looking through a microscope, or analysing patterns of symptoms. They need to be part of a chain that makes sure that families are supported while they live with no diagnosis, and to do that, they need to recognise what that means, and they won’t until someone starts telling them.

Finding a voice has always been the difficulty though. The key to highlighting the issues surrounding families lost in the diagnostic system is bringing them together and give individuals a unifying structure under which they can feel empowered enough to try and implement change. I have talked about the Lottery funded SWAN UK (Syndromes Without a Name) project run by the Genetics Alliance in previous posts. This is the first step towards changing the way we think about waiting for a diagnosis and making clinicians and government departments realise that structures of support should not fall into place once a diagnosis is able to be written in the right box, as a lot of families will hit crisis point either emotionally or financially before a diagnosis is found. Similarly, improving communication links between different departments can only be beneficial to hospitals and families alike. Something as simple as structuring and coordinating the complexities of testing and, more importantly for families, delivering the results of those tests in a timely manner would in itself reduce the stress of the process for everyone involved. As I have said previously, information is power, and parents are simply trying to make sense of what is a terrifying experience for them. Giving information enables them to make informed choices, feel more in control and less vulnerable. And baby steps are being taken, the internet is an underappreciated source of information and support and the fact that, almost exactly a year after SWAN was restarted (having petered out some time before) families are gradually being found and ideas of how things could change to more greatly support them are taking shape. I’m hoping that by this time next year, I will be able to confidently say that most families who leave a diagnostic appointment having failed to find an answer will do so clutching, at the very least, a leaflet telling them all about the rest of us out there, not because the doctors have been told to hand them out, but because they value the importance of a support network for their patients.

In the long term it would be good to add structure to the main specialist hospitals, bringing different teams together in order to better utilise resources and improve communication and information sharing. Central to this would be providing a family coordinator, which has already proven to successful for other organisations.

But what relevance does this have for me and my little family right now, since our appointment has past? Well at the moment I’m knee deep in paperwork convincing a faceless panel that they should pay money that they don’t want to pay to enable Dominic to stay at school. I guess what I’m saying is, despite it all, life goes on (as do the battles to give Dominic the life his peers enjoy automatically). Far from being annoyed by this, I think it’s a good thing. I don’t think there is any advantage to be had in dwelling on something that has past unless you are learning from it, and my attention is currently well focused if all my work positively influences events yet to come.

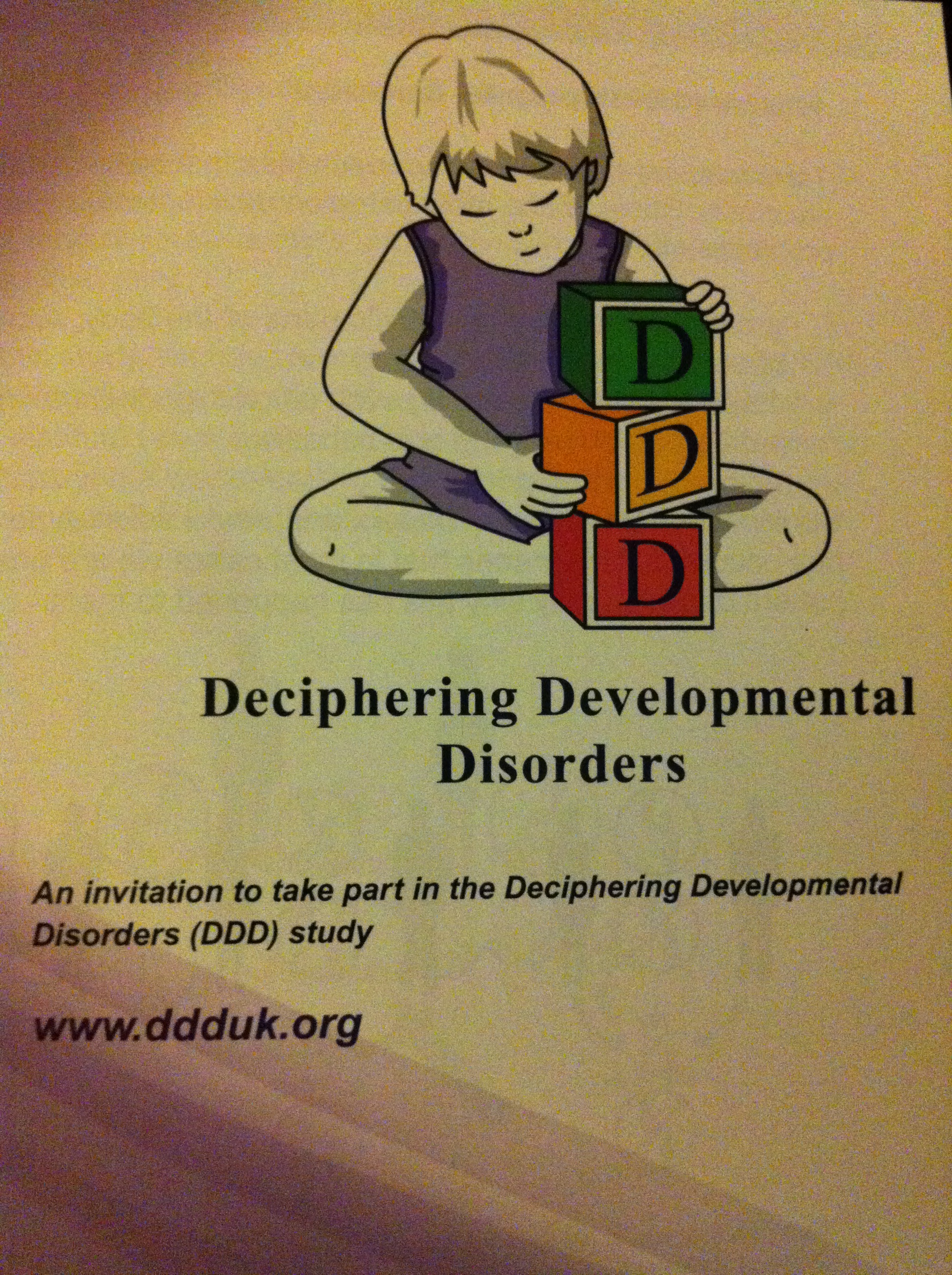

An invitation that could hold the key for so many undiagnosed children

Although I have openly said that I think that more support needs to be in place within the diagnostic departments for families that they see, I will admit that having come through the last 5 years on my own I have learn a valuable lesson that probably helps me more than anything else. I have learnt to assume the worst when it comes to dealing with the more practical side of Dominic’s journey through life. Now this probably sounds horrifically pessimistic, but I would argue that it is in fact simply realistic. By assuming that things won’t go as I hope, or that obstacles will be put in our way, I have learnt to always have a backup plan. The early years of being Dominic’s parent were a brutal lesson in survival, but as a result I am quite proud of my ability to think laterally about problems we’re faced with and to produce evidence that dots its i‘s and crosses its t‘s. It was thanks to the information that SWAN shared with its families about a new genetic study that was going on that meant that I had already mapped out my next step before I even entered the waiting room on the day of the appointment. Weeks before we went to the hospital, I had already written the relevant emails to persuade the relevant people to get us an appointment that I hoped would lead to Dominic joining the most exciting study ever embarked upon for undiagnosed children (in my humble opinion). I received the letter inviting Dominic to join the study two days ago. I truly think that this will help shape the way children like Dominic are diagnosed in the future, and would urge any parents in a similar position to go and take a peek at what the study is trying to achieve here.

For me, having access to information was key in enabling me to feel more in control of a system that is not kind to families who are reliant on it to work efficiently. This information should be freely available to all families in the same situation, as should the support that surrounds it. For a small amount of work, the benefits to both the patients and the clinicians are inevitable. A beautiful example of this was when, as I was gathering my things readying myself to leave the appointment, I mentioned to the CMS team that I had made an appointment with the genetics team and Dominic had been accepted into the DDD study. Interestingly enough the CMS team were fascinated to learn about the study and especially the implications that the results might hold for Dominic and other children they might see like him. They have taken details of the study so they can follow Dominic’s results. This is a beautiful demonstration of the potential value of bringing diagnostic services together to work in collaboration and share information between themselves and the families which move between them.

Professionals dealing with medically complex children have to remember that the human brain is hardwired to try and make sense of the world. It’s why if you lie back and stare at the clouds you will see images of things you recognise. It is no surprise that parents are frustrated and upset when all the pieces of their child don’t come together to make a recognisable picture and there is no one that you can look to in order to find out what the picture should be. Sometimes being unique can mean being lonely, and for a long time before I started writing Just Bring the Chocolate I was searching for others like us. This time last year I first shared my feelings about how it felt to have a child with no diagnosis and it feels like a lot has changed in that short time. No family should be allowed to walk out of an appointment and return to a life where they feel utterly alone and utterly lost. We can do better than that, and what’s more, we can give these families a voice and help not only advocate for their child, but for themselves too.

And us? Well we are simply carrying on our journey, now with three medical mysteries. But for the first time I’m actually excited by what the future holds for children like mine and by the positive influence that I can perhaps have on that. You see, I may have walked out of the appointment feeling defeated, but rather than giving up, what has actually happened is that it has proven a point to me. It has reminded me exactly why I don’t want to waste my energy simply complaining that things aren’t right, I want to help make them right. So you see, I may not have got the answers I was expecting at the appointment, but I have learnt that sometimes in life, you don’t get the answers you were looking for, you find the questions you should be asking.

Liked that? Try one of these...

I wanna scream for you! What bugs me about this Renata, is that the way you write shows me you are a pretty intellegent human being! What happens when someone has a child without diagnosis and is fighting the system, but isn’t so able to understand it all? (I’m not saying you understand it all, but you can probably make some sense out of it at least!).

I really enjoy reading your blog, and also find it educational. I’ve considered in my life what families who have a seriously ill child go through, things like cancer, cystic fibrosis etc, but I’ve never realised how not knowing can so affect a family before. Thank you for opening up your world and being so honest.

Finally, British rail need a kick up the butt!

Argh, that reads wrong there! I know what I mean by “educational”! Just doesn’t sound right though, sorry! I guess it’s given me a glimpse in to what your family and others in a similar situation actually go through.

@Susan Cuin I know exactly what you mean Susan, and educational is a good thing 🙂 Thanks so much for the lovely comment x

If you haven’t been told this today, you are amazing. You inspire me daily and I am lucky to have you in my life, no matter how virtually.

I am so sorry to hear that your much anticipated appointment has generated more questions (shrugs, blank looks and resulting chocolate/wine consumption) than answers. I still can’t imagine what that is like, not having a name for what is happening to your family. Knowing that my son has ‘Down Syndrome’ at least provides some comfort; I know (generally) what to expect. The general public (although their information and understanding of DS is probably 50+ years old and 3/4 conjecture) have an idea; at least it’s a term they’ve heard before.

Much love to your and your precious family. xox

@JenLogan Thanks Jen. I know from having talked to people that they find having a diagnosis a burden, as doctors won’t look beyond the text book understanding of the condition, so it’s swings and roundabouts. I don’t think you can ever make things ideal for families, diagnosed or not, but you can certainly make the process slightly less frustrating and confusing. And anyway, I truely think that doctors need to realise that patients are an undervalued resource, you get them together and information is shared and doctors benefit at the end of the day. Patients (and their parents) have a lot more emotionally invested in finding answers, so they are often the most dedicated of the people researching an answer, and linking in with others all over the internet means that information is shared more quickly than waiting on official medical papers to be written.

You’re always so kind, thank you for your support x

Inspirational 🙂 You are indeed amazing 🙂 I agree with Susan below, having fought (as you know) for my kids it has struck me time and again how different things would have been for them (and me) if I was unable to do so.

Incidentally – did you know there is a bigger discount on a “Friends and Family” railcard than a disabled one? Says it all 🙁 Disabled people cannot go on a train without a carer, you cannot push yourself safely around Liverpool St, on and off trains etc!! The carer’s card should be FREE!

@ekthompson Kate, that thought scares me, goodness only knows what would have happened if I couldn’t advocate for him *shudder*. Yeah, British Rail could make quite a few improvements…

Hi! I work with the Brilliance in Blogging Awards and I just wanted to say… well done on being voted as a finalist!!! The finalists are listed here:

http://www.britmumsblog.com/bib-awards/2012-bibs-finalists/

Feel free to email me for more information 🙂

@Michelloui *squeal* thank you!

Brilliant post (as usual!)

@SWAN UK Thank you x

A moving post as always, Renata. What strikes me, despite the fact we are in different countries, is that there is an apathy within the public eye here as well. We have more legalized accommodations, yet more publicly willing to roll their eyes or dismiss a child’s special needs in favor of withholding support and otherwise denigrating a family.

In our house, we’re going through the diagnosis merry-go-round yet again. It’s hampered this time, though, because we were abruptly cut off from all medical insurance for the kids at the start of this month – we had a disagreement over whether I had turned in a paper, and they won the argument. Because it makes so much sense for three boys with multiple diagnoses and (apparently) more to come to not need services any longer. *grr*

{{hugs}} You are a strong woman and I feel lucky to know you!

@KatMoody What a nightmare 🙁 I’m so pleased that we have the NHS, I often say how much harder our lives would be if we had to battle with insurance companies as well

Hi Renata, I had been looking out for your follow up about “that appointment” and thought I had missed it so I was so glad today when I had a bit of time to search that I found it. What an amazing job you have done once again. So in awe of your ability to craft your words and thoughts so eloquently. I read your recount which moved me to tears and promptly bashed my husband repeatedly, asking him to read. He is not normally a reader of all things blog like but I knew this would resonate with him as much as it did with me. We have had 5 trips to GOSH this year so far (no mean feat as we live in Jersey and have 3 other children so the expense/organisational aspects are fairly enormous) and so far at 4 of these appointments/procedures, they have lost results/given incorrect information resulting in tests having to be cancelled/postponed etc, cut short meetings because they were over-booked and changed what they intended to do in said meeting or clinic at the drop of a hat…..frustrating is not even close to an adequate description… I compare myself to the buttons on a school blazer – When we first started this journey just over 3 years ago, we were shining brightly, held together by many threads, proudly positioned and ready to face the world…now, we are held on by safety pins, a bit chipped, dented and rusty, definitely not fitting in the correct place and minus at least 2 down the front somewhere…….we feel guilty because we know we “are lucky that whatever Amelia has is quite mild” (as the medical professionals may delight in telling us) but so worried about what/where the future lies and getting her the appropriate help/care she needs as things change and move on. As ever, you summed it all up and we wish you well with the DDD study, fingers crossed!!

Firstly I want to completely agree with you about the rail service. I often travel alone (powerchair) and it can be a nightmare, the number of trains I’ve been left on, I remember having to stick my leg out of the door at my destination station as the train was about to depart, but no-one had come to rescue me with their ramp.

I mostly do long distance trains, and they tend to know where the disabled carriage is, I think it’s Peterborough that actually have markings for it, so I don’t know why they can’t do it in London for you. Maybe it’s the mindset of those in London. I had a nightmare trying to get a train within London once, the person at the desk refused to get me the ramp, told me to ask the driver, who said I had to ask the receptionist…..

I can understand the frustrations of not getting any further after, although you try not to, building up your hopes that you’ll get news, a way forward, anything to show that they might know what to do with you. Although not the same, I spent 5 years with the wrong diagnosis- I had to fight the system to see someone that specialised in the condition it was suggested by many that I had. The condition I was originally diagnosed with is looked on by many Doctors with scorn, and the day I got my new diagnosis, I celebrated not because it has a better prognosis, far from it, but because I knew what I was dealing with, the Doctors knew as well and it has made my treatment so much better. I hope that you can get to that stage soon with all the children.

Quality of treatment shouldn’t have to rely on a diagnosis, but the symptoms, the needs of the person involved, quality of life, etc… It frustrates me immensely, so I can only imagine it is multiplied for you.

Thinking of you all.