The Zulu Principle

“This [was]… an idea I had after observing my wife read a four-page article in Reader’s Digest on the subject of Zulus. As a result, within a few minutes she knew more than I did about Zulus and it occurred to me that, if she had then borrowed all the available books on Zulus from the local library, she would have become the leading expert in the county. If she has subsequently been invited to stay on a Zulu kraal (by an unsuspecting chief) and read about the history of Zulus at Johannesburg University for another six months, she would have become one of the leading experts in the world.

The key point is that my wife would have applied a disproportionate effort to becoming relatively expert in a very narrow subject. She would have used a laser beam rather than a scattergun and her intellectual and other resources would, in that narrow context, have been used to maximum advantage… That way, you will become relatively expert in your chosen area. It is only necessary to be six inches taller than the other people in a room to see above everyone’s heads. Applying The Zulu Principle helps you grow these extra six inches.” Jim Slater

I think Mrs Renata Mahoney has a nice ring to it, don’t you?

All through school various teachers and careers advisors asked me what I wanted to do once I had finished university in order that I might go on to be a useful member of society. I of course always envisioned that I would have a career, even if I hadn’t worked out the finer details of what I would actually be doing for my pay check each month. I was certain, however, that it would of course be something desperately worthy, I would most likely marry a poet or someone equally predisposed to ponder on life’s many complexities (and probably have leanings towards dressing in custom Delta sorority jackets with patches on the sleeves). I dreamt, like everyone else, of achieving great things in whatever I chose to do, but, beyond the rather bizarre pick of probable partner I had assumed I’d end up with, I’d not really got a goal in mind that I was aiming for like the slew of future doctors and solicitors that left school at the same time as me. So I set about studying A levels and a degree that was not career focused, but was simply the subjects I found most interesting and stretched my brain in enjoyable ways. It wasn’t that I hadn’t thought about it, just that I liked the sound of a lot of things and anyway the word ‘career’ sounded a bit dull and not enough like the sort of thing someone who was destined to change the world should be limiting themselves to. I did, after all, own a pair of bright green DMs and an attitude that generally presented the world with my best I’m-very-disappointed face before drinking myself under a table somewhere.

I’ve been playing with the idea of what I would grow up to become ever since I first let my imagination lose itself in a good film. With hindsight, a greater consideration was perhaps given to those jobs that featured in whatever happened to be a box office hit at the time. Police Academy sold the idea of being a policewoman in a best-buds-fighting-crime-and-having-a-laugh kind of way that appealed to me. I could quite clearly see myself protecting the mean streets of Hertfordshire with all the kooky charm of Mahoney. I had pretentions of edginess as well though, which is perhaps why the idea of living outside society like Kiefer Sutherland in the Lost Boys seemed like a valid career choice at the time. After much consideration, and just a little bit of smooshing my face up against Kiefer’s on the poster that hung on my bedroom wall, I had to tearfully accept that being a vampire really isn’t a great profession for a right on vegetarian such as myself, however many ways you try and convince yourself otherwise. I wasn’t entirely sure I could pull off the required mullet with the right amount of passive aggressive disregard for fashion with my frizzy hair anyway. Ghost Busters offered more career possibilities in this specialised area, and I figured that it was not actually necessary to run around in a jumpsuit as it was possible to be a serious scientist who simply studied things that aren’t there (yes there is an interesting non sequitur there isn’t there). No really though, you can actually study parapsychology, at an actual university should you chose to spend your life pursuing this as a career, and there is not a jumpsuit in sight.

I don’t think it would have be classed as a vocation

I did (briefly) dally with the possibility of being a nun when I first saw The Sound of Music, The idea of not having to tame my hair each morning seemed like a good starting point, especially if it meant that I could also sing as beautifully as Julie Andrews. This carer path was again considered when I saw how much fun they appeared to have in Sister Act, but did wonder if being an atheist might reduce its potential to be a long term career choice. Anyway, I wasn’t sure that I’d ever seen Mother Teresa spontaneously bursting into song at any point, so perhaps the singing and dancing nuns were in the minority. Knowing my luck I would have been put with ones that actually had to pray and go to church, could you imagine?!

Teaching? Well yes of course teaching came up, with my love of English literature and Robin Williams’ brilliant performance in Dead Poets Society, I did think that it would be unfair to not go and rescue the depressed public school boys with rousing poetry readings and lessons in self belief. I was convinced that I would be that inspirational teacher that are so prevalent in films, but more of a scarcity in schools. With the exception of the brief period after Pretty Woman was released [ahem] and you could pretty much summarise my dalliance with possible careers for myself as having a general theme when I was younger. I wasn’t interested in making money, I just wanted my job to count for something. In my own, impossibly idealistic way, I just wanted to make the world a better place.

What actually happened to me was the non-Hollywood version of the above. My first proper job, rather bizarrely considering that I did an English and drama degree, was in surgical theatres. Sadly working in the surgical department did not surround me with perfect specimens of hair coiffure and dazzlingly white teeth, and we certainly did not go home at the end of each day having learnt a deep and meaningful lesson about ourselves or our colleagues. Instead we left thinking that (most of) the surgeons were arrogant pricks and that perhaps the memory of that afternoon’s proctology list might be washed away (so to speak) with a stiff drink, if you weren’t on call of course. Only the consultants were allowed to answer the bleeps using the pub phone.  The fact that I didn’t share a theatre with McDreamy wasn’t the only reason I swapped my beloved scrubs for the scratchy green shirt and trousers of the London Ambulance Service (which were about as far from being provocatively figure hugging as in the Police Academy’s version above as is fabrically possible) and attempt to haul enormous steel capped boots and all necessary equipment up 12 flights of urinals stairs to treat patients on the top floor because someone accidently broke the lift by repeatedly slamming a metal bar into it (which would probably be classed as a mercy killing considering the toxicity levels of the air should the lift doors ever be capable of closing once again).

The fact that I didn’t share a theatre with McDreamy wasn’t the only reason I swapped my beloved scrubs for the scratchy green shirt and trousers of the London Ambulance Service (which were about as far from being provocatively figure hugging as in the Police Academy’s version above as is fabrically possible) and attempt to haul enormous steel capped boots and all necessary equipment up 12 flights of urinals stairs to treat patients on the top floor because someone accidently broke the lift by repeatedly slamming a metal bar into it (which would probably be classed as a mercy killing considering the toxicity levels of the air should the lift doors ever be capable of closing once again).

I’m not sure if people who had the propensity to want to slowly eat themselves to death purposely move to the top floor of the most inaccessible buildings in London, or whether it is simply living there that drives them to console themselves with endless éclairs, but inevitably I’d arrive at the flat dragging a chair and blanket and enormous medical kit experiencing more convincing chest pains than the person that we were about to attempt to carry back down again. During my time with the London Ambulance Service I neither changed the world, nor was the least bit worthy, but I did love piecing the puzzles together of the ailments that the patients presented with. Unless those ailments smelt, then, admittedly, I was slightly less keen.

My pregnancy with Elliot saw me based back in hospitals, setting up the PALS (patient advice and listening service) for my local area with a small team of others. The principle of the service was sound, the difficulty was the people who used it. Generally speaking it was the people who moaned so much that their spouses had widowed them just to get a break from it that would pick up the phone to bend my ear. I spent a remarkable amount of my time with my head on the desk listening to people moan about inconsequential fixtures and fittings around the hospital and trying not to sigh too audibly. There was a fair amount of damage control at the maternity ward to be done, but any brilliant plans of action I may have offered the women fizzled out the second my stomach entered the room a few seconds before I did. Somehow telling a heavily pregnant woman of the trauma you’ve just been through at the hands of the maternity service doesn’t sit well with some, which is bizarre considering the amount of mothers that do so relish the look of horror as they recount their stories in gruesome details for all the mums-to-be. I hope the kinks have been since ironed out and the service is actually being used by people who should be speaking up about their experiences. I know plenty of people who have had great success with PALS. Personally, when I tried them out as a ‘user’ I’d have been better spending my time rolling bogies and flicking them at the people that needed a kick up the bum than bothering with asking the branch of PALS that I approached to intervene on my behalf. But I recognise that this is not indicative of the service as a whole.

My period of being paid to be polite to people (that the rest of the world wants to be rude to) came to an abrupt end when I wandered down to the maternity department, ankles sloshing with the amount of oedematous water in them, thinking that the stars and spots swimming in front of my eyes didn’t bode well. After that I very quickly, and rather brutally became a mother and that’s when the Zulu principle and I first met.

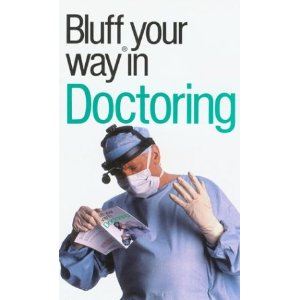

Becoming a mother is an assault on every one of your senses, it’s an exercise in surviving mental torture and has a learning curve that puts a banana to shame. Yet, at the same time I learnt so much about such specialised things that, if you pitted my knowledge against the general public’s on the same subject and you would have to concede that I, in the context of the wider world, was a childcare expert, and really that’s something that more mothers should learn to be proud of (Gina Ford, eat your heart out). Ok, so perhaps being an expert in cloth nappies or the various colours and textures of poo when your child can’t tolerate certain foods isn’t something that you’d necessarily write on a CV, but if you’re a diehard know-it-all like me, approaching changes in your life by embracing your inner nerd and studying your arse off to lessen the chances of you getting caught off guard, is simply a time consuming, but effective, coping strategy. It also happens to help you win arguments, and be generally known as a smug know-it-all bastard. Or perhaps that’s just me. Becoming an expert is not particularly difficult when your child is as complex as Dominic, though. The likelihood of anyone knowing what the hell you’re talking about is about 1 in a thousand, unless you’re standing in a specialist hospital, then it is perhaps 1 in 100. Not that this makes the remotest bit of difference to how doctors treat me, even when I’m spelling things out for them to go and google, the expected patient-doctor dynamic, plays itself out, despite my obvious expertise in my specialist subject (which is Dominic, if you hadn’t guessed). Now before you hurrumph at me and call me arrogant, I should perhaps insert a disclaimer.  I’m not claiming to know more about medicine than the lovely doctors who look after my wonky kids. I am claiming that, when you compare me to the general population, I know a hell of a lot more about the things that are wrong with Dominic than the average person. That, by default makes me a expert. I do however know a lot more about Dominic than any other person, which means I consider myself the leading expert, and I have yet to understand why much of the medical profession still find the idea of parents being valued as the most experienced experts in the team looking after a child such a difficult concept to work with. Are their egos really so fragile, or are they simply still basing their standard of expected simpering on such classics as Carry on Matron?

I’m not claiming to know more about medicine than the lovely doctors who look after my wonky kids. I am claiming that, when you compare me to the general population, I know a hell of a lot more about the things that are wrong with Dominic than the average person. That, by default makes me a expert. I do however know a lot more about Dominic than any other person, which means I consider myself the leading expert, and I have yet to understand why much of the medical profession still find the idea of parents being valued as the most experienced experts in the team looking after a child such a difficult concept to work with. Are their egos really so fragile, or are they simply still basing their standard of expected simpering on such classics as Carry on Matron?

Obviously with Dominic being an over achiever, I am now professing to be an expert in a rich array of different fields, some of which I have listed below (which is rather a wrapped way of bragging, admittedly):

Specialist seating, manual wheelchairs, power chairs, nasal feeding tubes, housing adaptations, surgical feeding tubes, reflux, intestinal dysmotility, various surgeries, living in hospital, specialist feeds, gut osmolality, reducing osmolality of feeds to more effectively hydrate a child, analysing gastric losses, replacing gastric losses, muscle biopsies, educational statementing, disability discrimination act, disorders of the neuromuscular junction, jumping queues at theme parks, pica, blue badges, tootie frooties etc etc etc

Of course, I’m not arrogant enough to say that I am more of an expert than those who have dedicated their lives to such subjects, but, using the Zulu principle, I know more than the vast majority of the general public. Therefore, by default, I am an expert.

Still don’t believe me? Ok, fine, let me tell you a story. During 2010 – 2011 I turned myself into more of an expert in using isotonic feeds as a way of reducing IV fluids in tube fed children than various nutritional experts at Great Ormond street. At least it appeared that way when, having been told that Dominic would have to go home on IV fluids after 8 months in hospital, I took the Zulu principle approach to the problem and spent the next few months researching a theory I had about how fluid is used in the body and how I could make the fluid we gave him be used more efficiently. After coming up with the theory, read everything that I could about rehydrating children in Africa, as no one had written anything about my particular problem outside of drought conditions, I set about trying to convince a resistant group of doctors to let me test my theory by having the labs analyse exactly what he was losing into his bile bag. I eventually succeeded in working out what he needed and shared my findings. I was told that the feed that I was proposing to create was impossible to make and would not work anyway. I then produced evidence of a feed used in other countries that was exactly what we needed, and that no one in GOSH had even heard of, but that would be ideal for a child like Dominic and plenty of other children in their care. They were delighted by the discovery of the feed, but went on to tell me that they couldn’t just ship it in as it wasn’t licensed in the UK, so I restarted my research to try and convince them to change the makeup of Dominic’s feed to make it as isotonic as possible and then replace a set amount of the liquid that he was getting via IV with dioralyte instead. I found a little known study done in Africa showing good results by attempting to reduce the osmolality of their patients feeds. Despite all the evidence that I had produced, and the fact that we had nothing to lose but everything to gain at that point, I still had to beg, cry, talk, convince, re-convince and then convince again to get anyone to even listen to me. They finally did and much to my delight my theory worked and his IV fluids were finally reduced each day until he no longer needed any IV support at all. The Zulu principle, in this case, stuck two fingers up at the people that were happy to settle for sending him home in a worse state than he arrived in. Yes they are the experts in nutrition and the inner workings of the gut. But I turned myself into the expert about how to use the osmolality of an enteral feed to reduce IV fluid support, simply because I learnt more about what was possible than anyone else involved. Therefore, by default, I was the expert. And I kicked butt.

The Zulu principle is a power tool for all mothers, especially mothers who have more of an invested interest in gaining knowledge about their child’s condition than the treating doctors do. And the doctors should never forget this, the parents are the experts about their children, and they are also the ones who are likely to go the extra mile to find an answer even when everyone else has given up. If I were immature enough to want to (figuratively) stick my tongue out at the people who forced me to become an expert in order to protect my child’s health, I would make a point of highlighting that despite the huge battle, resulting negativity and emotional cost of fighting the perception that I was ‘just’ the mother (so therefore simply a passive bystander in my son’s care)- here we are, a year later, not having been on IV fluids or having had a long stay in hospital since. But I’m way more mature than that.

Undoubtedly I have become far more of an expert on a far wider range of things ever since I stopped trying to be an expert at anything important, or at least anything that pays the bills. The fact that this expertise is so rarely recognised means that I do still feel like I have to justify the fact that I do still have a brain, to myself as well as the people I come in contact with on a day to day basis. There is always that awkward pause, after the question, “Sooooo…. what do you do?”. When I answer that I look after my children full time, I might as well have say that I sit around in my pyjamas all day, eating chocolate cake, dropping fag ash on the baby and catching up with the paternity test results on Jeremy Kyle, as you gain no respect by raising children over having a career. I recognise that it’s as much my perception of myself as anyone else’s though. It’s hard to bolster your feelings of self worth when everyone is being introduced by their name and then profession at a meeting and you are then added on as an afterthought as “…and mum”. It wouldn’t be quite so condescending if it wasn’t for the simple fact that, at most meetings that I attend, the majority of the expertise being shared is mine, yet I am still defined, to some degree (in almost all the specialities that we deal with) by the outdated notion that the paid expert adopts the paternalistic role and the unpaid expert adopts a passive compliant one. Having a career makes people take you seriously, and it troubles me that it grates more and more on me as time goes on, especially as being in a position to get a job (where my contribution is actually valued) is still a long way off. Perhaps being an expert at becoming an expert in times of need should be a how I introduce myself from now on. Or else I should perhaps just simply remind the person that says “… and mum” that I’m far too young and good looking to be their mother, and reintroduce myself as Renata, the one expert in the room who has decided to spend their career specialising in the subject that we’re all there to discuss. Ok, so perhaps you wouldn’t call raising my children a career, it’s certainly a valid job though, and who knows what the future may hold for me as far as finding a paid job that fits around Dominic goes. Maybe explore new career opportunities abroad and Trouvez un emploi pour expatriés grâce à https://euworkers.fr. I do know, however, that even though the job that I’ve ended up with doesn’t exactly pay well, it is dripping with worthiness, it does make good use of all the skills I’ve learnt in my various jobs beforehand, but most importantly it undoubtedly makes the world a better place, for one little boy anyway.

Want one of my cards?

Liked that? Try one of these...

Not liking he is stuck in hosp 🙁 but liking the sparkly clean chair and looking forward to new blog :))

Hear Hear! I go all coy when I’m praised for being such an expert on my child, where would she be without me etc. because I feel it’s something any half decent parent would do by default. Your beautifully written post makes me feel proud of what we do for our special kids. x

@jane_gregory thank you Jane, I’m a bit the same which is ridiculous considering how annoying I find it when people don’t appreciate how much input I have. I’m not easy to please I guess! And you should be proud, you’ve done far more than just raise your daughter, you’re now a successful writer and going on to raise awareness to help others x

Actually Renata I think that’s *EXACTLY* how you should introduce yourself at the next meeting!

@liz marcy I’m sure it would cause a very long, very awkward silence before everyone mentally marked me as the ‘mum with a chip on her shoulder’ and pretended it hadn’t happened 🙂

That needs to go in some medical journals

Loved reading this Renata a brilliant post and I like the card!. Being a Mum is one of the hardest jobs in the world but it is also the best and the most rewarding. ps I have to say that being a Grandmother is amazing too! xx

@AnneHawkes Glad to hear it Anne, I fully intend to force my children to have children of their own so I can ruin them and then hand them back to wreak their revenge on their parents 🙂

I love the idea that you are an expert in tootie frooties as well as everything that goes with special needs. A great read 🙂

@Blue Sky Ahh yes, I have done much eating in order to fully research the subject 🙂

Love it:) A very good Dr some years ago once told me after months of being fobbed off “that there was nothing wrong with my son” and I was being “an over-anxious first time mother” (actually he had a perforated ear drum but that’s another story) that we may not have medical degrees but as parents we generally spend the most time with our kids and if your gut feeling is that something is wrong, then shout and scream for all your worth until someone listens for you are invariably right! Probably the most useful piece of “medical” advice I have ever been given!

@LisaB very true Lisa. We know every hair and freckle on their bodies, and if something isn’t right, we’d be the first to spot it. I’ve had the ‘over-anxious 1st time mother speech too. When I told them he was my third, I got told not to compare him to my others as all children are different. You can’t win sometimes!

Really thought-provoking xxx